Steve Katz, way back in

2011, wrote

about what his students wanted from an eText. Their

suggestions / requests included:

- Video

- Links to sources

- Activities they can download

- Intuitive navigation (like a web page)

- Loads quickly

- Customizable fonts

- Adjustable page size

- Colorful

- Searchable

- Links to sites of experts on the topic

- Question and answer section where they can post and respond

- Live chat with other students and recognized experts

- Rollover of terms to see the definition

- Linked table of contents

- Printable pages

- Voice controls

I considered this list in terms of what the author of a work can do

(content, design, styles) and what is more dependent on the reader

machine or software (that is, Nook, Kindle, PC, smart phone, etc.)

supporting that feature. There is of course some overlap —

videos and downloadable activities, for example, both require the

author to include them and the machine or software to support

them. However their relationship to the eText itself is

different. The activities are a bonus, whereas the video is

presumably meant to be watched directly in the eText, as part of the

eText.

Anyhow, the point is just that some of these requirements can

logically be considered in different ways. Because we are

considering the author's contributions here, especially style and

design, I am not going to worry too much about the other cases.

So, it seems that six of the elements are exclusively under the

control of the author. They are:

- Links to sites of experts on the topic (content)

- Links to sources (content)

- Video (content)

- Colorful (design)

- Intuitive navigation (like a web page) (design)

- Linked table of contents (design)

Three are basically about the content (content) the author includes and the

other three involve design choices (design), also made by the author.

I think these are the most important for us to focus on (at this

point at least). Before doing so, however, I will briefly explain

how I categorize the other elements.

A few other elements require both design or style considerations

and support from the machine and software displaying the book. They

are:

- Adjustable page size

- Customizable fonts

- Printable pages

- Rollover of terms to see the definition

The last one, rollover of terms to see the definition

is

perhaps the clearest example of what I am talking about. Unless the

reading software is already designed to look up any word, the author must

include some definition (or a link to the definition) for the words

most likely to be looked up.

However, even if I provide definitions, if the software does not

support popping up a small definition bubble on mouse hover or through

a click event, then my work is wasted. Thus, both software and content

support is required for this feature. The author only has direct

control over one of these.

The same is true for the other three that require both machine /

software support and the author's design or style support. Most ebooks

formats that I am familiar with already allow various fonts and font

sizes. However, as the author, if I set the defaults improperly, or

assume a specific page width for things like pictures, charts, and the

such, what the students get on the printed page may not be what they

expected.

Below are six elements that are more dependent on the machine or the

software displaying the eText.

- Activities they can download

- Live chat with other students and recognized experts

- Loads quickly

- Question and answer section where they can post and respond

- Searchable

- Voice controls

These six I believe to be mostly dependent on factors external to the

author. A question and answer section that allows students to post and

respond sounds a lot like a social media site of some sort (once

known as "message boards" or "forums"). Search is an awesome feature

for a text, but realistically is best left to the device displaying

the content. The same is true of voice control.

Back to the six most dependent on the author:

- Links to sites of experts on the topic (content)

- Links to sources (content)

- Video (content)

- Colorful (design)

- Intuitive navigation (like a web page) (design)

- Linked table of contents (design)

The first two are fairly obvious and important to include. Video may

seem strange because I listed activities as an element that is also

dependent on the machine or software. The difference is that the video

is intended to be played while in the book whereas the activities were

specifically mentioned as being for download. The important thing, I

think, is that the work should include appropriate videos that help

the learners master the content. We can create these and it shouldn't

be too difficult to include them in an eText — web sites today

routinely include (perhaps too many) videos. (However, to be safe, an

author may also want to include a fallback for the event that the video

is unavailable or unable to be displayed.)

The other three are design choices. When poorly done, in my limited

experience, problems often come from people thinking of only one way of

interacting with their text.

- The table of contents does not have links to jump to each chapter?

- The author probably expected students to print the book.

- Are the links colorful and underlined?

- The author probably did not expect students to print the book or

did not think about how expensive color printing can be.

- Images or other graphics that extend across several pages or that

overflow for text?

- The author may have written for one device without checking how it

looked on other devices.

These sorts of design problems are exactly what website designers

have been dealing with for many years. In fact, several popular ebook

formats are basically just web pages. They use plain text with

markup languages (such as XML), style sheets, and maybe some

javascript, to handle the formatting and presentation of the content.

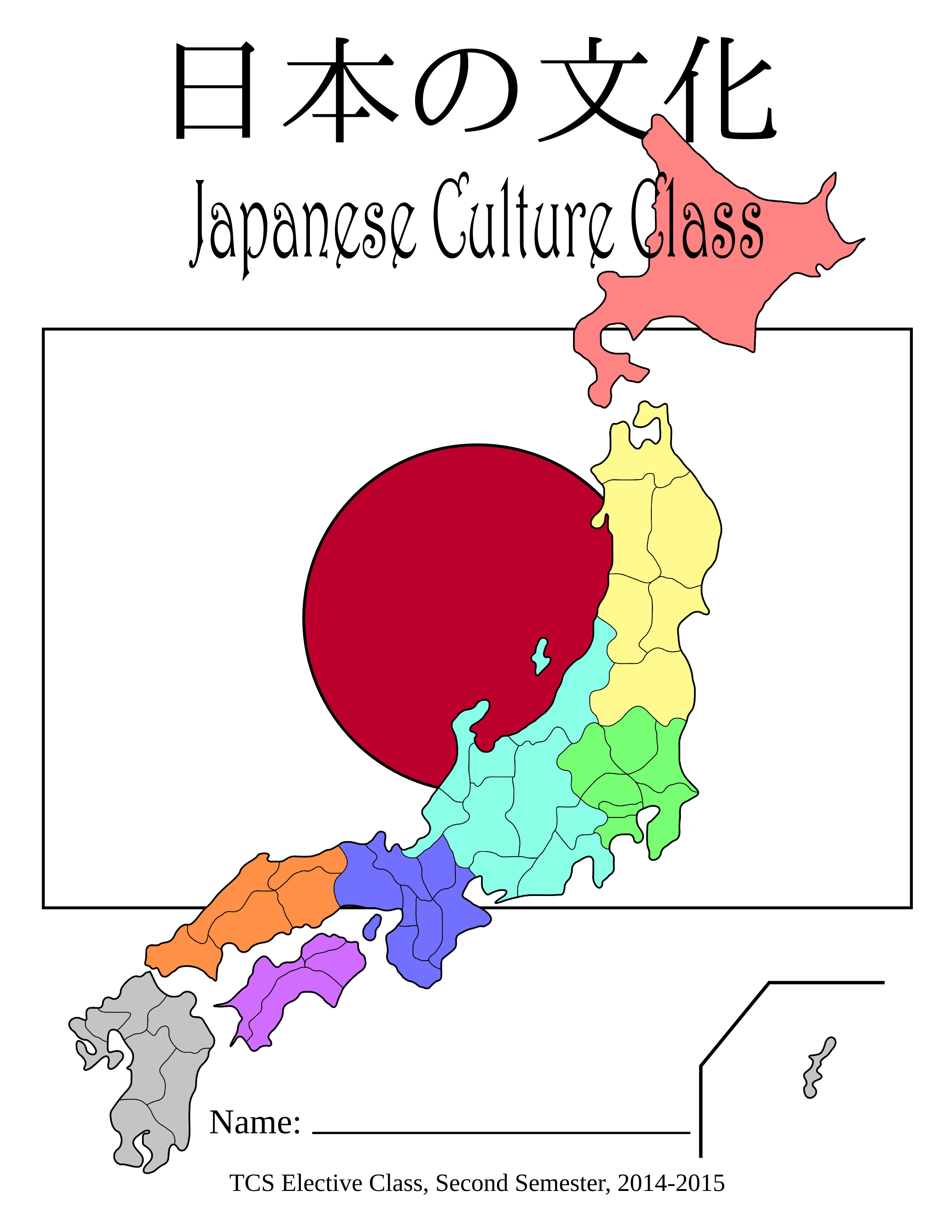

Below is part of my current print-oriented text for a Japanese

Culture elective. It is currently in Scribus format for export to

PDF, but in anticipation of converting it into an eText, I have

redone part of it into this HTML file (aka web page). The sections

"Introduction" and "The Japanese Language" Have content. The Table

of Contents includes every section currently in the book. I tried to

hit several of the elements discussed above, mostly using actual

content (such as embedding videos) and styles, but time caught up

with me, so there is not as much of either (yet) as I would

like.

Some of the content is originally from Wikipedia and has been

modified by me. The images of hiragana and katakana are also from

Wikipedia. (Will update with links very soon.)

To see how the text can be presented in different ways, open this

page in either Firefox or Opera. There are four extra styles in

addition to the main (default) style. I threw them together pretty

quickly and have not done all that is possible to complete them,

much less perfect them. Hopefully, though, they highlight somewhat

the possibilities and the points discussed above.

In Firefox, go to View → Style

Sheet, and choose from the four listed below "Basic Page Style". If

you reload the page, Firefox will default back to the basic page

style.

In Opera, go to View → Style, and try the four way at the

bottom.

Chrome does not seem to support changing style sheets, so it won't

work with this example. I do not use MS IE and do not have it, so I

cannot test this page in it. Same situation with Safari — I

don't have it and don't use it, so I cannot say if it will work. If

you do have Safari or MSIE, please try it and let me know. In the

real world, you might be able to use javascript to have any browser

load a different style.

The print style sheet is what modern browsers should use

automagically when the user prints the page. This is where you take

out unnecessary images and color. You also hide elements such as

videos and replace them with (for example) a link, a thumbnail

image, and a description. Funky fonts should also be replaced with

ones good for reading on paper. Ideally, vocabulary popups could be

replaced with [definitions in brackets after the word] or perhaps

placed as endnotes.

The accessibility style sheet is similar — contrast is

increased and fonts are slightly bigger. However, this is still

intended for the screen, so video is not hidden and links are made

more colorful, not less.

Mobile friendly tries to optimize the page for small screens. Among

other things, use of 100% of the screen is allowed. Also, images

should load at smaller sizes, but with Javascript, you could have

the page load an image that is actually smaller, which would save

bandwidth and memory, and allow the page to load more quickly.

Cool and Colorful

is just playful but tries to show some of

the things you can do with styling. (You might even see poorly done

columns.) If Javascript were included, readers could change fonts

and colors on the fly without having to reload different style

sheets.

These are just examples, and not necessarily great ones. Modern

browsers should present most web pages in pretty much the same way,

but apps and mobile browsers may not. Devices may not support as

many style options, and may not support javascript (or elements such

as video) at all.

We are going to talk about and experience various aspects of Japanese

culture in this class. First though, here are a few things you should

know as we get started.

Names and forms of address

Maybe you have heard that in Japanese, “san” gets put at the end of

names and means something like “mister” or “misses”. This is true, but

unlike mister and misses, “san” can be used with either your given

(first) name or your family (last) name. So “Joe-san” and “Smith-san”

are both okay.

We call medical doctors “Dr. Smith” in English, not “Mr. Smith”. The

same is true in Japanese, except that the list of people you call

“doctor” is longer. “Sensei” doesn't mean “doctor” exactly—in fact

it means “teacher”—but you use “sensei” instead of “san” with

doctors, lawyers, teachers, and several other highly skilled and

respected professions.

When in doubt, “san” is probably a safe way to address someone, unless

that person is a teacher or doctor, then you use “sensei”.

In school, “san” is used by adults mostly toward other adults (who are

not teachers) and toward female students. A teacher would call Akiko

(a girl) “Akiko-san”. Teachers would also call adults (parents,

visitors to the school, etc.) “san” also, whether male or

female. Teachers have another way to refer to male students: “kun”. So

teachers would call Akira (a boy) “Akira-kun” when talking to him or

about him. Actually, many adults (not just teachers) would use “kun”

with boys and young men.

There would be a video here. In

theory, when printed the video and this text should not print,

instead an alternative paragraph, showing a link to the video and a

short description would print. Currently, reality may not match

theory.

There was a video here. To watch it, return to this page, or

visit:

(video link here)

Other students would call Akira “Akira-san” if they were in the same

grade. Friends and people much older (like grandparents) often use

“chan”, to show affection. Boys would probably not call each other

“Akira-chan” or “Taro-chan” but they might be called that by their

girlfriends. Likewise, Akira might call his girlfriend “Akiko-chan”.

In Japan, not using anything after a name is considered very

rude. When you use someone's name, you always need to add “san”,

“kun”, or “chan”, or “sensei” (teacher) after the name. Using the

wrong one, however, can be almost as bad as not using anything.

In Japan, age, occupation, and status level (rank) are very

important. In fact, it is normal for people to call others by their

job title or the person's situation (like “customer-san”,

“foreigner-san”, or “patient-san”). This is true in school, too.

Most students take part in school clubs and there is a strict

hierarchy. Anyone who is ahead of you in school is called

“sempai”. Students below you are called “kohai” if they are not called

by their family name. Unless they hold a position above you (like

captain of your team), students in the same grade can call each other

by family name or a nickname, but they would still usually include

“san”.

In Japan, names are Family Name first and then Given Name. So I am

Spackman Chris in Japan. This is why I do not say “first name” or

“last name” — it is very easy to get confused about which name you

mean when dealing with Japanese names.

Japanese Culture

As you may have figured out from the discussion of names, Japanese

culture is very different from “Western” culture. Different does not

mean better or worse, though. Some things that the Japanese do will

probably seem strange and even non-sensical to USA Americans; the

reverse is certainly true. We must understand that judging another

culture is a meaningless waste of our time (and insulting to the

culture being “judged”). Every culture starts from different

assumptions and different views of the world. No culture is logical or

consistent.

What we must do is accept Japanese culture, learn about it, and by

doing so, learn more about our own culture. For example, the fact that

the Japanese language has words for relationships such as “sempai” and

“kohai” tells us something about Japanese culture. Now that we know

that, we can reflect on the fact that English-language USA culture

does not use words like “sempai” and “kohai”. We will be doing a lot

of this sort of comparison during this class.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

The Japanese language is very different from English, French, Spanish,

or any other European language. Because Japan is very far from Europe,

Japanese speakers did not have much interaction with speakers of

European languages until just the last couple of hundred years. This

means that the Japanese language shares very few words with other

languages, aside from Chinese and Korean — her nearest neighbors,

geographically and linguistically.

The English language, in contrast, has many words that came into

English from French, German, Latin, Greek, and other European

languages. This is one reason why there are so many cognates among

European languages. (In the last hundred years, however, the situation

has changed and today many words have entered Japanese from

English. Many, however, are words for specific items that didn't exist

in Japan 100 years ago — for example, ‘pasokon’ for personal computer,

‘isu kohi’ for iced coffee. There are many more, but the point is that

these cognates are unlikely to help you learn the language, although

they may help you order your breakfast at a donut shop.

Despite Japanese being very different from English, it is actually not

a difficult language to pronounce. There are only five vowel sounds —

English has more than 10! — and also unlike English, words are written

almost exactly how they sound. Once you get used to the sounds,

spelling words is easy!

Unlike English, Japanese has only two irregular verbs. How many does

English have? Hundreds. Two examples: run → ran, throw →

threw. Japanese has only two — the verbs “to do” (suru) and “to come”

(kuru). These two verbs are used so much in Japanese, that you will

probably get used to them very quickly and soon forget that they are

technically “irregular”.

The Japanese alphabet is not difficult either. There are two systems

of writing Japanese letters: hiragana and katakana. They are a bit

different: hiragana is used more frequently and is more rounded, a bit

like cursive in English; katakana is used only in certain situations

and looks blockier, less rounded. Both hiragana and katakana have

about 48 letters (the same 48 sounds in both, just like “e” “E” are

the same sound in English). Learning both systems requires remembering

about 96 letters.

Does that sound difficult? If so, stop and think about English for a

moment. How many English letters can you read and write? Upper and

lower case each have 26 letters — so 52 total. Can you also read

cursive writing? That is another 52 letters — so to read upper and

lower case in both print/block style and cursive style in English

requires knowing 104 letters. When you think about it like that, 96

for Japanese is not quite as bad as it might sound at first.

The bad news, of course, is that Japanese also has kanji, Chinese

characters, and there are almost 2000 that everyone learns in school

and must know be able to read a newspaper. We will not be learning all

of them in this class.

Hiragana, with stroke order

The worse news is that each of those kanji can be combined with one or

more other kanji to form a new word that may not have any connection

to the meanings of the kanji that make it up. For example, the word

for “newspaper” is “shimbun” 新聞 but 新 means “new” and 聞 means

“hear”. Even if you know both of those kanji individually, you may not

have any idea what they mean together. You need to know thousands of

these combinations in order to graduate high school and be able to

read a newspaper! It takes a long time to get to that point — Japanese

students start learning kanji in first grade and learn a few each year

through the end of high school. Also, they have the advantage of

already knowing all the vocabulary as well — they already know the

word “shimbun”, even if they cannot read the kanji. Native English

speakers need to learn both the word “shimbun” and the individual

kanji and then the combination.

Katakana, with stroke order

All of the above is just the tip of the iceberg (not the culture

iceberg, the proverbial iceberg) when it comes to the Japanese

language. It is very different from English, so if English is your

native language, you may find Japanese a lot difficult. To be fair,

many Japanese students find English very difficult, and they are

usually required to study it for close 8 to 10 years!

The two graphics show how to

write hiragana

and katakana. The numbers and arrows

show the order and direction that you should write each line. Take a

good look at the tables. What can you deduce about Japanese? Why are

some squares blank? What sounds would the blank squares stand for, if

there were letters for them?

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents